Film Transcript

Click here to download the film transcript as a PDF file.

NARRATIVE SCRIPT

Voice of David Douglas

“…We can be carried into regions where we contemplate the most glorious workmanship of nature, and where the dullest imagination becomes excited. We can travel through distant lands and become acquainted with the complexions and the feelings and the characters of mankind, under every form of life.” David Douglas, 1833

Narrator

At the dawn of the 19th century, Europe was reaping the benefits of discoveries and knowledge gained during the Age of Enlightenment. New scientific advances enabled the Great Explorers to reach distant lands. But the New World was still largely uncharted. The wilderness of western North America was contested and not yet part of the United States.

A young man from Scotland named David Douglas was to become an unlikely but passionate trailblazer. He would explore and learn from the land in a way that no European had done before. Today, his contributions are all around us. His efforts have transformed gardens and forests throughout the world. And the everlasting monument to his work is the tree named in his honor—the Douglas fir.

TITLE: FINDING DAVID DOUGLAS

Narrator

When David Douglas was born in 1799, many of the rolling hills of the Scottish countryside were nearly barren. The native forests had largely disappeared due to the practice of felling trees to raise crops and graze animals to support a growing population. But as a boy, David Douglas would have had no awareness of such things. There were still enough woodlands and streams near his rural home in Perthshire to captivate his imagination.

His father, John Douglas, was a stonemason, helping to construct the new palace in the village of Scone. As a working class family, the Douglases could only afford the basic necessities. But Scotland, unlike other countries, provided widely available public education. So the Douglas children were able to attend school, where they learned to read and write.

But even as a young lad, David Douglas was restless. He preferred nature to the confines of the classroom. During his 3-mile trek to school, he would get so caught up in the wonders of plant and animal life along the way that he often wouldn’t make it to class. He was much more interested in fishing or bird watching or collecting plants. He would find wild owls and adopt them as pets—and then, instead of buying food for himself, he would spend his only lunch penny on meat to feed them.

At home, he and his siblings were encouraged by their mother to read the Bible. But Douglas would also devour books of adventure and travels to far-away places. Robinson Crusoe and Sinbad the Sailor were his favorites.

It was not likely that Douglas would ever get to see the distant places he dreamed of. As the son of a stonemason, he would go to work at an early age. And so it was that he left school at the age of eleven and went to work as an apprentice gardener.

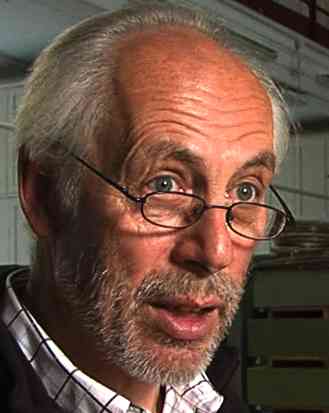

Gordon Mason

By eleven he'd left school and was apprenticed as a gardener in the grounds of Scone Palace. But he was clearly identified as someone who was bright and capable and was, if you like, taken under the wing of the local aristocrats and given access to their library of botanical references, and I think this helped to set Douglas on his career path as a plant collector.

Narrator

Through hard work, self-study and perseverance, Douglas rose to a succession of better positions. By the time he was 20, he’d acquired enough skill and experience to become qualified for a job at the prestigious Glasgow Botanic Gardens. Here, he was noticed by the renowned botany professor, William Jackson Hooker. Hooker admired the young gardener’s deep knowledge, curiosity and boundless enthusiasm. He became a friend and mentor to Douglas, inviting him on botanical explorations in the Highlands of Scotland.

Gordon Mason

That early direction that Hooker, seeing how effective Douglas was, how hard working he was, and how at home in the wild—plant collecting in the wild—how effective Douglas would be for the Horticultural Society collecting on the other side of the known world.

Narrator

Plant hunters were seeking plants that could be of use, in everything from medicine to commerce. By sending out plant collectors, the Horticultural Society of London looked to expand scientific knowledge of the world’s plant kingdom. The Society also stood to make a handsome profit on sales of new plants to wealthy landowners. People who could afford it were eager to keep up with fashion by displaying the latest botanical discoveries in their own gardens.

Based on Hooker’s recommendation, the Horticultural Society chose David Douglas in 1823 to sail to the east coast of the United States to find new specimens of trees and plants that would grow well in England. Douglas proved so successful on this assignment that the Society proposed to send him out on a much more perilous mission, collecting specimens in the uncharted territory of Northwest America.

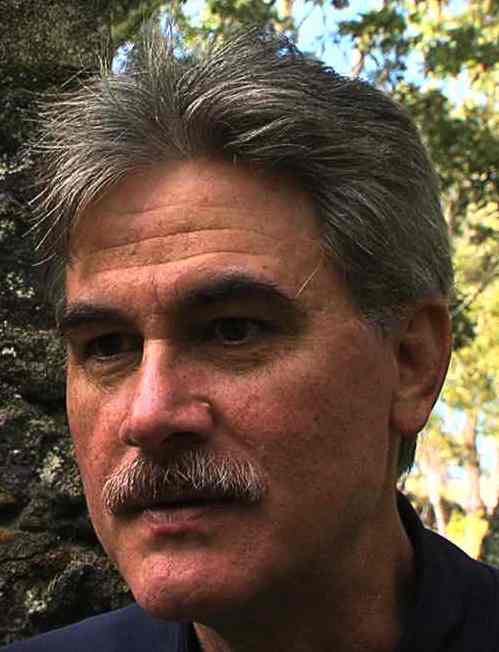

Syd House

Plant hunting was a pretty dangerous exercise. The average life expectancy of plant hunters of that time was around a year. Because inevitably you were going to dangerous places, not many other human beings around or if there were other human beings around they might well be hostile to you.

Tony Kirkham

The early plant collectors were the ones that went through really tough conditions. They were going to parts of the world that nobody knew. And people like Hooker were looking for people that wanted to go off and explore and that was the key thing—these people had to want to go.

Narrator

Douglas wanted more than anything to go and prove himself worthy of the new challenge. In July of 1824, Douglas’s older brother John saw him off at the port just outside London. They both knew that this might be their final farewell.

The voyage to the west coast of North America would be long and difficult. The ship had to sail all the way south around Cape Horn and back up the Pacific. Arrival was never guaranteed. And while earlier scientific expeditions to the Pacific Northwest had been made by Archibald Menzies and Lewis and Clark—the vast interior regions remained completely unexplored by Euro-Americans. For Douglas, it was a journey into the great unknown.

His employers did fear that he might be too timid and shy to be successful on this expedition. He was, in the words of the Society’s President, “the shyest being almost that I ever saw.” But Douglas had shown himself to be a hard worker and he was willing to take the risk when others were not.

Eight months passed on the rough seas. Once the destination was in sight, hurricane-force storms prevented the crossing of the treacherous sandbar at the mouth of the Columbia River. Douglas faced another six weeks of anticipation before it was finally safe enough to reach land.

At last, on April 7th, the ship sailed into Baker’s Bay and anchored in calm waters. David Douglas had no way of knowing what to expect during his one-year assignment. But he couldn’t wait to get started.

Voice of David Douglas

April 7th, 1825. With truth, I may count this as one of the happy moments of my life. As might naturally be supposed, to enjoy the sight of land, free of the excessive noise and motion of the ship—from all deprived nearly nine months—was to me truly a luxury.

Narrator

He’d barely taken his first step on the river’s shore, when he seized upon his first botanical find. He recognized salal from an earlier description by Archibald Menzies, a fellow Scot. Relating the moment of discovery in his journal, Douglas could hardly contain his excitement.

Voice of David Douglas

On stepping on the shore Gaultheria shallon was the first plant I took in my hands. So pleased was I that I could scarcely see anything but it. Mr. Menzies correctly observes that it grows under thick pine forests in great luxuriance and would make a valuable addition to our gardens.

Narrator

The first people to greet Douglas from the ship were Indians who lived near by, bringing dried salmon and other goods to barter. Douglas knew that he must have appeared strange to them, with his eyeglasses and odd habits.

Voice of David Douglas

The natives viewed us with curiosity and put to us many questions. Some of them have a few words of English and by the assistance of signing make themselves very well understood.

Narrator

Douglas was aware that relations between the Indians and Europeans were volatile and could turn dangerous at a moment’s notice. But he needed their help to do his work. He would also be assisted by the resources of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Hudson’s Bay Company was a British trading firm profiting from the sale of furs to European markets. The vast enterprise stretched across the continent with a network of forts and trading posts. The Company served the imperial interests of England and they were willing to help Douglas by providing lodging, horses and other support he needed.

The chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, Dr. John McLoughlin, came downriver to meet Douglas and take him back to the Company’s new western headquarters, Fort Vancouver. When he arrived at Fort Vancouver, Douglas was preparing to become the first scientific traveler to live in the region. He joined a diverse group of Hudson’s Bay Company employees: Scots, English, French-Canadians, Iroquois, Hawaiians and local Indians living and working there.

Narrator

With Fort Vancouver as his home base, Douglas would take excursions for days or weeks at a time to collect in the lower Columbia River region. He meticulously kept a field journal for his employers. A typical journal entry would not have been as personal as the letters he wrote, but it would serve as a detailed record of his journeys and botanical finds.

Voice of David Douglas

The scenery in many parts is exceedingly grand. And on the banks of the river the rocks rise perpendicularly to the height of several hundred feet in some parts, over which are some fine waterfalls.

Syd House

The Pacific Northwest has some interesting climatic and geographical similarities to Western Europe. It roughly parallels the same latitude, range of latitude. That range of habitats, that similarity with Europe and the British Isles in particular, means the two areas are a great parallel for growing plants.

Tony Kirkham

When Douglas went to the west coast of North America, he realized that he was almost at home, that he was, he could have been in Perth. And that any trees or any plants that he collected there would grow in the gardens at Scone and other places.

Voice of David Douglas

During my journey I collected the following plants, some very interesting and will, I am sure, amuse the lovers of plants at home: Spirea, plentiful on the rapids; grows very luxuriant in low, damp, shady woods. Clarkia puchella, annual; flowers rose color; abundant on the dry sandy plains near the Great Falls; an exceedingly beautiful plant. I hope it may grow in England. Campanula, perennial; flowers blue; rocky situations near the Rapids.

Gordon Mason

The herbarium is a collection of dried plant specimens. And this one is absolutely huge. It’s got 7 million specimens. And the particular specimens I've got here are from the 1820s and 1830s, collected by David Douglas himself. We've got here, Ribes sanguineum, which every gardener in the U.K. and Europe will recognize as the flowering currant. This is an original from David Douglas, the second plant he collected in the Pacific Northwest in 1825. He'd be delighted that this plant has become so popular. And then, we've actually got here the sort of equipment Douglas would use. This is what he would have used in the field and the basic design of a plant press hasn't changed these last 200 years.

David Harris

We take the plants in the field, we put them in a piece of newspaper, and put some blotting paper around them, strap them up in a press like that. This would be a press very similar to one that Douglas would have carried. And then we’d dry that over artificial heat. So he’d probably put that over a campfire and the specimens would be dry in a couple of days. This is called a vasculum. It’s like a tin lunchbox, and Douglas would have used one of these himself. In the past we used to carry these into the field, so people would be collecting very delicate plants. And they would put them inside this container, and close it up, and uh they would be able to carry that. And then they would be able to bring it back to their base camp and work on it.

Narrator

Whether he traveled by canoe, horse, or on foot, Douglas was so intent on finding new specimens of plants, that he often didn’t stop to eat or rest.

Gordon Mason

He was traveling very hard, very rough with what nowadays we would regard as completely inadequate amounts of food. And he covered vast distances in his travels.

Voice of David Douglas

I had to cross a plain 19 miles without a drop of water, thermometer in the shade 97 degrees and scarcely can I tell the state of my feet in the evening, all the upper part of them were in one blister.

Ann Lindsay

He didn’t just go the extra mile, he went the extra 100 miles. And he was interested in such a wide range of his surroundings. In fact, he was the Renaissance Man of the Earth.

Not only was interested and hugely knowledgeable about plants and could go back months later when he’d seen a plant and find the seeds and know how to grow it and save it, but he also brought back more plants than any of the other plant collectors.

Narrator

In his first six months in the Pacific Northwest, Douglas gathered an extraordinary number of specimens: 499 species, with up to 24 samples of each one. Among his finds during this period were Oregon grape and Sitka spruce. Douglas seemed determined to prove that he could collect more plants than anyone else, no matter what it took.

Rémy Claire

David Douglas was a what you’d call today a complete naturalist. He was also interested in volcanology, in geology, in biology. Everything was of interest to him.

Narrator

In a letter, George Barnston, an employee at Fort Vancouver, related the extent of Douglas’s passion:

“One morning a large specimen was brought into our square, and we all had a hearty laugh at the eagerness with which the Botanist pounced upon it. In a very short time he had it almost in his embraces fathoming its stretch of wings, and he found it a full nine feet from tip to tip. This satisfied him, and the bird was carefully transferred to his studio for the purpose of being stuffed. In all that pertained to nature and science he was a perfect enthusiast.”

Rémy Claire

He was a man of science and what this guy wrote in his papers when he described the potentialities of the different tree species, which were growing in the Pacific Northwest, are just marvelous.

Gordon Mason

David Douglas certainly had his travails with the weather. He records on a number of occasions that he was drenched to the skin after a long day's travel, absolutely soaked to the skin and was then obliged to sit up most of the night drying specimens that he'd collected. He would press them during the day or as he was going along between sheets of absorbent paper. Of course the absorbent paper absorbed all the rain that fell on him, and he spent more time drying his plants than he did sleeping.

Narrator

Despite his constant battles with the weather and rough terrain, Douglas persevered. The thrill of discovery had a firm grip on him. He remained a dutiful employee trying hard to impress the Horticultural Society. If he had appeared shy to his employers in Britain, here he seemed to be assertive and in his element. Douglas was resourceful. He knew that the native people had great wisdom regarding the land. He saw that his capacity to do his work could be enhanced by what they had to teach him. In order to communicate better with the local Indian tribes along the river, he learned to speak Chinook Jargon.

Gordon Mason

He had a generally good relationship, probably an above-average relationship, with the local population, because they had things that he wanted. They had knowledge of where plants grew, and I think that they regarded him as a distinctly odd character. Their local name for him was “the Grass Man” because, in their eyes, he was going along collecting grass and what could be more ordinary than grass. Why did you need to collect it. . .they knew what it was called, it was called grass.

Voice of David Douglas

I visited Cockqua, the principal chief of the Chinook tribes. My Indian friend afforded me the most comfortable meal I’d had for a considerable time before, from the spine and head of the fish. He was at war with the Clatsop tribe, inhabitants of the opposite banks of the river, and that night expected an attack. He pressed me hard to sleep in his lodge lest anything should befall me. This offer I would have most gladly accepted, but as fear should never be shown, I slept in my tent fifty yards from the village. In the evening about 300 men danced the war dance and sang several death songs. In the morning he said I was a great chief, for I was not afraid of the Clatsops.

Narrator

When summer turned to fall, Douglas began to collect seeds. He needed to keep the seeds dry so they could make it back to London in viable condition. He divided them into separate batches, sending them back by different routes to increase the odds that at least some of them would make it.

But his usual optimism began to fade in early October. He’d been preparing boxes of specimens when he stumbled and his left knee came down hard on a rusty nail. A disabling infection followed. The weather was turning even more rainy and cold and the pain and stiffness in his knee plagued him. By the time he returned to the fort in mid-November, with very little to show for his efforts, Douglas was clearly dejected.

Voice of David Douglas

I arrived again at Fort Vancouver at half past eleven at night, being absent 25 days, during which I experienced more fatigue and misery, and gleaned less than in any trip I have had in the country.

Narrator

Douglas wouldn’t be collecting during the winter. He remained at the fort and by the time the holidays arrived, he was miserable. His knee was still so painful, he couldn’t participate in Christmas Day activities. Then came an even greater disappointment. The annual post arrived—bringing him nothing.

Voice of David Douglas

I learned with much regret that there were no letters, parcels or any article for me. I was given to understand they left Hudsons Bay before the arrival of the ship, which left London the May before, so that if Mr. Sabine wrote to me, the letter will remain on the other side of the continent til next November. I was exceedingly disappointed.

Gordon Mason

I think without doubt he was often quite lonely with only his Indians for whom he had only a rudimentary grasp of the language, and his journal for company. He had little news of home because communication in those days was pretty rudimentary. It more or less had to go down the Atlantic, round Cape Horn and back up the Pacific Coast. Letters from home routinely took a year to reach him.

Voice of David Douglas

Sunday, January 1st, 1826. Commencing a year in such a far removed corner of the earth, where I am nearly destitute of civilized society, there is some scope for reflection. In 1824, I was on the Atlantic on my way to England; 1825, between the island of Juan Fernandez and the Galapagos in the Pacific; I am now here, and God only knows where I may be the next. In all probability, if a change does not take place, I will shortly be consigned to the tomb. I am in my twenty-seventh year.

Narrator

As bleak as Douglas’s state of mind seemed in the depths of a hard winter, his low mood lifted with the coming of spring. He recognized the extraordinary opportunity he had been given and there was so much more he wanted to do. His year in the Oregon country was supposed to be coming to an end. But Douglas took a bold step. He decided to disregard the agreement with his employer and not return to Britain for another year. He wrote a letter to Joseph Sabine, secretary of the Horticultural Society, explaining his actions.

Voice of David Douglas

February, 1826. From what I’ve seen of the country and what I have been able to do, there is still much to be done; after a careful consideration as to the propriety of remaining for a season longer than instructed to do, I have resolved not to leave for another year to come. Lest the former should be made any objection to, most cheerfully will I labor for this year without any remuneration, if I get only wherewith to purchase a little clothing.

Narrator

Now that Douglas was staying, he would have the time and freedom to explore farther into the vast interior region of the Columbia Basin. He departed Fort Vancouver in March, traveling in company with 14 men and two boats for an extended journey to the dry regions east and north. In anticipation of the five-month trip, he carried 102 pounds of pressing paper. To make room for the paper, he barely took any clothes. The terrain and vegetation were like nothing he’d yet seen. The dry landscape created fertile ground for many unique species. Douglas found Ponderosa pine and sagebrush.

Narrator

With little regard for his own physical comfort, he forged ahead.

Voice of David Douglas

My eyes began to trouble me much. The wind blowing the sand and the sun’s reflection from it is of great detriment to me. Returned at four in the afternoon fatigued, my eyes so inflamed and painful that I can scarcely see directly an object 10 yards distant.

Narrator

Douglas spent several more weeks botanizing in the region, despite a lack of food and his numerous physical complaints. Traveling back through The Dalles, he noticed smoke rising in the distance and thought he’d find Indians and have salmon to eat. Instead, he encountered Hudson’s Bay Company fur traders. They were carrying his long-awaited letters from England, two years after leaving home.

Voice of David Douglas

There is a sensation felt upon receiving news after such a long silence, and in such a remote corner of the globe more easily felt than described. I am not ashamed to say (although it may be thought weakness by some), I rose from my mat four different times during the night to read my letters; in fact, before morning I might say I had them by heart. My eyes never closed.

Narrator

Returning down river to Fort Vancouver at the end of August, Douglas traversed nearly 800 miles of the Columbia region in 12 days. By mid-September, 1826, Douglas was ready to venture out again, this time to look for a tree he had been hoping to find for a very long time. He’d seen an incredible pine cone measuring 16 and a half inches long. He believed it must belong to the grandest species of pine he could imagine. He joined a fur brigade and set out in search of the sugar pine.

Narrator

It was a difficult journey through the Willamette Valley. A grizzly bear attacked the group. Deer were scarce and there was little else to eat.

Ed Alverson

Here on the Finley Wildlife Refuge we’re standing in an area of wet prairie that’s changed very little since David Douglas walked by here—probably within a mile or two of here—in October of 1826. And that was in the fall, and it was different for him because the prairie grasses had been burned off by the Indians, and he wasn’t able to find a lot of seeds or a lot of plant specimens in most areas.

The tarweed was an important plant for the Native Americans. They harvest the seeds. Once the seeds mature the fires that the Native Americans would set would burn through the prairie but leave the tarweed stock still standing. And the seed heads would still hold the seeds and uh they’re roasted and ready to eat, and no sticky tar anymore. So we’re really standing in wet prairie, but we’re also standing in what was the grocery store for the Indians—it was a place that they valued and also took a lot of care of.

Narrator

Five weeks after setting out, they finally arrived in the Umpqua Valley. Douglas continued on alone to look for the sugar pine.

Robert Kentta

Eight years before David Douglas showed up here in the Umpqua Valley, there was Hudson’s Bay Company activity here and a also some free trappers that were unaffiliated with Hudson’s Bay Company. And there was a battle or a massacre of some sort that happened, and there was about fourteen Umpqua people killed. And so those experiences taught Indian people to be cautious.

Narrator

Douglas was in completely unfamiliar territory. When he encountered an Umpqua Indian near his camp, they were unable to understand each other through language. Instead, Douglas drew a picture of what he was searching for.

Voice of David Douglas

With my pencil, I made a rough sketch of the cone and the pine I wanted and showed him it. He instantly pointed to the hills about 15 to 20 miles to the south.

Narrator

Douglas headed in that direction. Before long, sugar pines were visible in the distance. They were the tallest trees that Douglas had ever seen.

Robert Kentta

Douglas arrives here and sees his first Sugar pine, and he couldn't find any examples right on the ground, but he could see cones that had already opened up on the tree. And so he's looking up in the tree, trying to figure out how to get 'em down and the only way he can figure out to get 'em down is to shoot 'em down.

Voice of David Douglas

Putting myself in possession of three cones—all I could—nearly brought my life to an end. Being unable to climb or hew down any, I took my gun and was busy clipping them from the branches with ball, when eight Indians came at the report of my gun.

Robert Kentta

After hearing a firearm go off, they came to check out immediately what was going on.

Voice of David Douglas

They were all painted with red earth, armed with bows, arrows, spears of bone and flint knives and seemed to me anything but friendly.

Robert Kentta

He eventually let down his guard a little bit and started trying to describe what it was he was after which was specimen cones, needles, and so forth.

Voice of David Douglas

I perceived one string his bow and another sharpen his flint knife with a pair of wooden pincers. I stood eight or ten minutes looking at them and they at me without a word passing.

Robert Kentta

I think their immediate reaction would have been—‘what would he want with the cones? The cones are worthless—he must want the seeds inside which we've just put a huge store of them away—we'll go get him some.'

Narrator

Douglas feared for his life. When the Indians went to get him some seeds, he decided to run.

Voice of David Douglas

I picked up my three cones and a few twigs and made a quick retreat to my camp, which I gained at dusk.

Narrator

Douglas was clearly unnerved, but avoiding further confrontation, he managed to leave with three prized cones.

Voice of David Douglas

When my people in England are made acquainted with my travels, they may perhaps think I have told them nothing but my miseries. That may be very correct, but I now know that such objects I am in quest of are not obtained without a share of labor, anxiety of mind and sometimes risk of personal safety.

Narrator

Douglas and his party returned to Fort Vancouver that fall. He worked diligently indoors through another cold, rainy winter, preparing for his journey home in the spring. He would join the Hudson’s Bay Company’s annual York Factory Express, a 3,000-mile overland expedition, by canoe and on foot, across North America to York Factory on Hudson Bay.

Syd House

York Factory is one of those mythical places. It’s a bit like Xanadu or Timbuktu. Somewhere you read about, and it conjures up an image of adventure. And going almost to the ends of the earth. It’s a really difficult place to get to.

Narrator

From York Factory David Douglas would catch his ship back to England.

Voice of David Douglas

Tuesday, March 20th. Preparations being made for the annual express across the continent. By five o’clock in the afternoon, I left Fort Vancouver for Hudson Bay. I glad that the time was come when my steps should once more be bent towards England.

Narrator

With the Express, Douglas set out from Fort Vancouver, following the Columbia River north by canoe.

Voice of David Douglas

April 30th, 1827. The snow four to six feet deep in the higher spots, the ravines or gullies unmeasurable. The snowshoes twisting and throwing the weary traveler down—and I speak as I feel—, so feeble that lie I must among the snow, like a broken-down wagon horse entangled in his harnessing. Obliged to camp at noon, two miles up the hill, all being weary. No water, melted snow, which makes good tea. Find no fault with the food. Glad of anything. Dreamed last night of being in Regent Street, London. Yet far distant. Progress nine miles.

Narrator

The brigade faced the challenge of crossing the Rocky Mountains on foot. The nine men carried heavy loads. In a tin box secured with an oilcloth, Douglas carried his seeds and journals, weighing forty-three pounds. They frequently missed the blaze marks on the trees and went off the path. But discomfort and fatigue did not dampen Douglas’s drive and spirit. At Athabasca Pass he went on to climb the highest mountain peaks alone. At Jasper House, the men loaded canoes and followed rivers and lakes to the flat prairie lands beyond. They often had to portage their canoes around dangerous waterfalls. At Fort Edmonton, a party was held in David Douglas’s honor. One of his traveling mates supplied the music on a violin.

Voice of David Douglas

Last night before we should part with our new friends, Mr. Ermatinger was called on to indulge us with a tune on the violin. No time was lost in forming a dance. And as I was given to understand, it was principally on my account. I could not do less than endeavor to please by jumping, for dance I could not.

Voice of David Douglas

Monday, August 27th, 1827. The idea of finishing my journey and expectations of hearing from England made the night pass swiftly. On sunrise on Tuesday, I had the pleasing scene of beholding York Factory two miles distant, the sun glittering on the roofs of the house (being covered with tin) and in the bay riding at anchor the Company’s ship from England.

Narrator

York Factory had been the Hudson’s Bay Company’s headquarters since 1682. In David Douglas’s day, it was a thriving, year-round community. Supply ships brought provisions and trade goods and returned to England with a year’s bounty of furs.

Narrator

During his two-and-a-half year journey in North America, Douglas covered nearly 10,000 miles. He would be returning to London having accomplished great things. Before leaving, Douglas was re-outfitted from the Company’s stores.

Gordon Mason

Well I’m sitting in the Hudson’s Bay Company archives in Winnipeg. This is the York Factory account book for 1827. We’ve actually got an account for David Douglas for the Horticultural Society. His material was worn out, he was worn out after his epic trek across the continent. He was quite literally in rags, and the Company outfitted him again. The first entry is a gallon of rum, this for a four-week journey back across the Atlantic to Britain. A gallon of rum is really rather a lot of rum to consume in a four-week journey. There are two separate entries for snuff. Toothbrush, soap, another beaver hat, and then we’ve actually got David Douglas’s underpants here. We have two pairs of white flannel drawers—only two pairs of underpants so he didn’t change them that frequently—dressing combs, galoshes, shoes, the princely total of 14 pounds, 14 shillings and thrupence on this account for David Douglas, getting back to the Horticultural Society.

Narrator

Back in London, Douglas was honored and praised. His plant discoveries were featured prominently in the leading botanical magazines of the day. But despite receiving the acclaim he’d worked so hard to earn, Douglas found he was unsatisfied.

Gordon Mason

We see a different side of Douglas when he eventually gets back to London after his expedition to the Pacific Northwest. He’s walked across the continent, exhausting himself in the process. When he eventually recovered, he found that although his introductions and his achievements were greatly valued in society, and he was lionized for a while and introduced to the great and the good and awarded fellowships in the Linnaean Society and the Horticultural Society. After a while it began to be obvious that his introductions were valued more than he, Douglas, was actually valued.

Narrator

Inspite of growing tensions between Douglas and the Horticultural Society, they did offer to publish his journal and let him keep the proceeds. But as he tried to prepare it for publication, it didn’t go well. He procrastinated. He was impatient, rude, and he stubbornly rejected help from almost everyone, including his boss, Joseph Sabine.

Syd House

When he found out that the doorman at the Horticultural Society was paid more, I think that’s what—uh—as we would say in Scotland, stuck in his craw—stuck in his throat. That uh, that was a difficult one for him to swallow. And that was the start of some of his disagreements with the Horticultural Society.

Narrator

It was clear that he wasn’t fitting in back in London. Douglas came to realize that exploring in the natural world was more important to him than fame and recognition. What he really wanted was to be sent out on another assignment. His friends wanted this for him, as well. “Qualified, as Mr. Douglas undoubtedly was, for a traveler,” wrote Dr. Hooker, “it was quite otherwise with him during his stay in his native land.”

Syd House

We see him comfortable in the frontier, comfortable in bettering himself when he was a young man, an apprentice gardener, and we see him comfortable now given a specific task and getting on with it. We see him uncomfortable when he’s operating in the more sophisticated world of the gentlemen gardeners and horticulturalists of the Horticultural Society, where he perhaps was not able to articulate his own views of things or to perhaps write perhaps as well as others who’d been educated differently.

Narrator

It was July 1829 before Dr. Hooker, working in the background on his friend’s behalf, persuaded the Society to send Douglas back to America. In preparation, Douglas spent four weeks at Greenwich Observatory, learning how to use the latest scientific instruments. This would also help him to do surveying for the British Government. Douglas plunged into his studies with enthusiasm, working up to 18 hours a day. Knowing he would soon be venturing out again, his behavior improved. In a letter to Dr. Hooker, he wrote:

Voice of David Douglas

I have had only one or two very slight outbreakings, as Mr. Sabine calls my fits, since I last saw you.

Narrator

With renewed purpose, David Douglas journeyed for a second time to the west coast of North America. This time the objective was to explore Spanish California. He would make his way to California, first via Hawaii and then Fort Vancouver, with his new traveling companion, a Scotch terrier named Billy. Billy would always be at his side keeping Douglas company throughout his journeys.

When the ship stopped in Honolulu, Douglas took the opportunity to botanize.

He was intrigued with Hawaii and determined to return for a longer visit if he could.

At Fort Vancouver, things were different. A terrible epidemic had decimated the native populations. Many Hudson’s Bay Company men had died, as well.

Voice of David Douglas

A dreadfully fatal intermittent fever broke out in the lower part of this river about eleven weeks ago, which has depopulated the country. Villages, which had afforded from one to two hundred effective warriors are totally gone. Not a soul remains. The houses are empty and flocks of famished dogs are howling about, while the dead bodies lie strewn in every direction on the sands of the river. I am one of the few persons among the Hudson’s Bay Company’s people that have stood it, and sometimes I think even I have got a shake, and can hardly consider myself out of danger.

Narrator

Douglas arrived in Spanish California in December 1829. The landscape opened up for him another exciting new world. His botanical finds included flowers, seaweeds, mosses and several species of pines. Delighted with his findings, he wrote to Dr. Hooker:

Voice of David Douglas

You will begin to think that I manufacture pines at my pleasure.

Narrator

As he traveled through the region, Douglas’s facility with language enabled him to communicate in Latin and Spanish. He stayed with the Franciscan friars along the El Camino Real. Douglas seemed quite content in California.

Voice of David Douglas

The ladies are handsome, of a dark olive brunette, with good teeth and the dark fine eyes, which bespeaks the descendant of Castille, Catalan or Leon. It is the land of the vine, the olive, the fig, the banana. The wine is excellent. Indeed, that word is too small for it, for it is very excellent.

Narrator

Douglas ended up spending thirty months in California. On his way back to Fort Vancouver, he learned that Joseph Sabine was blamed for the Horticultural Society’s poor financial situation and was forced to resign. Out of loyalty to his longtime supporter, Douglas resigned, as well.

Now traveling as a free agent without the backing of the Horticultural Society, Douglas was planning his biggest challenge yet. He’d long thought about returning to England by walking across Siberia. He sent word of his plans to Dr. Hooker.

Voice of David Douglas

What a glorious prospect. Thus not only the plants but a series of observations may be produced, the work of the same individual on both continents, with the same instruments under similar circumstances and in corresponding latitudes.

Narrator

He set out for Russian Alaska with a group of Hudson’s Bay Company men, traveling as far as Fort St. James. By the time they arrived there, 1000 miles north of Fort Vancouver, Douglas realized he was isolated. To get to the Russian headquarters at Sitka, he would have to travel without support through little known territory where the Indians were considered very dangerous.

For once, he gave up and began to retrace his steps to Fort Vancouver.

Just days later, on June 13th, 1833, disaster struck on the rocky islands of the Fraser River at Fort George Canyon. His canoe was smashed to pieces, and Douglas barely escaped with his life.

Gordon Mason

With the benefit of hindsight, we can see precisely the point at which it all started to go wrong for Douglas, traveling down the Fraser River, with the fruits of several years' hard labor—with specimens, with seed collections which it had taken some seasons to collect, and of course with the journal. And the journal was THE journal, there was only one journal, there was only one copy of it, and virtually all of that was lost.

Narrator

His journal and specimens were gone forever. All that we know of his travels and scientific endeavors from 1829 to 1834 we know from his letters.

Gordon Mason

Douglas, much disheartened, was obliged to retreat back to Fort Vancouver and, looking through the letters and odd bits of communication that we have from him then, it's clear that the stuffing’s been knocked out of him, the spirit has gone out of him. His eyesight's failing. His right eye by this time is completely blinded, and his left eye is beginning to fail. And bear in mind he's only 34 years old.

Narrator

Douglas decided it was time to return to England and that en route he could visit Hawaii again. He arrived in Honolulu for Christmas and headed to the Big Island just after New Year’s, 1834. He was determined to climb Hawaii’s volcanoes, using his instruments to take scientific observations during his ascent. At Kilauea, he witnessed the rumbling of the earth and the flow of the molten lava. The immense power of nature never failed to fill him with reverential awe.

Gordon Mason

So he retreats eventually back to Hawaii, and he was the first European to climb Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea and did both of those in the space of a month, and both of those are big expeditions from sea level to somewhere in the region of 14,000 feet. And he's exhausted himself, frankly, exhausted physically and mentally.

Narrator

Having accomplished his goal of climbing Hawaii’s highest peaks, Douglas was ready to go home. Looking forward to seeing Dr. Hooker again, Douglas writes what would be his final letter.

Voice of David Douglas

I visited also the volcano of Kilauea, the lateral volcano of Mauna Loa. It is nearly nine miles around, one thousand one hundred and fifty-seven feet deep, and is likewise in a terrific state of activity.

May God grant me a safe return to England. I cannot but indulge the pleasing hope of being soon able, in person, to thank you for the signal kindness you have ever shown me. And really, were it only for the letters you have bestowed on me during my voyage, you should have a thousand thanks from me.

Jeff DePonte

There it is. Right there under the pines. We’re here at the 6,000-foot level of the northwest slope of Mauna Kea at a place that’s called Kaluakauka, or the Doctor’s Pit. This is the place where David Douglas died, July 12, 1834. Douglas was making his way from Waimea to Hilo that day, and he’d spent the night at the home of a man named Ned Gurney, who was originally a convict from Australia. It’s not even clear I don’t think how he got to Hawaii, whether he escaped from Australia and made his way here. It was known that Douglas did have a purse with some coins with him, and he always traveled with his little Scottie dog and um, I guess Ned Gurney the convict um says he wanted to show him the bullock pits where he trapped these large bulls. The method of capturing them was to dig a pit and somehow lure the bulls, maybe cover it over, or whatever. And that’s where Douglas’s body was later found, in the bottom of one of these bull pits, with a bull standing over him.

Narrator

When Douglas’s body was recovered his money was missing. Many in Hawaii believed that Ned Gurney had robbed and murdered him, but the medical report was inconclusive. The controversy over the cause of death continues to this day. Douglas was buried at Honolulu’s Kawaiaha’o Church in a ceremony attended by nearly all of the town’s foreign residents. Douglas’s faithful little terrier, Billy, was sent back to London and adopted by a clerk in the British Foreign Office.

Jeff DePonte

One of the ironies is that here where Douglas died these Douglas fir trees live. The man who built the monument brought either seedlings or seeds and planted these fir trees, and now they grow here standing guard over his monument.

Narrator

At first, David Douglas’s introductions were treasured for their beauty and their grandness. But in time, more practical uses for the trees were found. Douglas always recognized the value of nature to mankind.

Syd House

He foresaw the benefit of the forests, and certainly in the trees, and particular Sitka spruce and Douglas fir, he foresaw the great role they could play in clothing the uplands, the Highlands of Scotland, just exactly the countryside you're looking behind me in his native Perthshire.

Narrator

Since David Douglas’s time, Scotland’s forest cover has nearly quadrupled. Trees introduced by Douglas are the mainstay of Scottish forestry. Today, we understand the importance of passing on this legacy to future generations.

In his short life, Douglas introduced more than 200 new species to the gardens and forests of Europe. He put his health and life at risk countless times in the pursuit of knowledge. David Douglas understood that natural resources must not be taken for granted, but utilized sensibly and with care. It’s fitting that his name lives on in a tree that towers over others in landscapes of North America and Europe, a tree he described as “one of the most striking and truly graceful objects in Nature.”

Interviews conducted by Lois Leonard, filmed and recorded with:

Gordon Mason, Botanist, Sheffield, England:

August 25, 2008, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

May 14, 2009, Studio 320, Kew, London, England

May 15, 2009, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Herbarium, London, England

Syd House, Conservator, Perth & Argyll Conservancy, Scottish Forest Commission, Perth, Scotland:

May 20, 2009, Perthshire, Scotland near Dunkeld

May 25, 2009, Almondbank nearby Perth, Scotland

Tony Kirkham, May 15, 2009, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Herbarium, London, England

David Harris, May 19, 2009, Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, Scotland

Ann Lindsay, May 20, 2009, Pitlochry, Scotland

Rémy Claire, May 22, 2009, Almondbank nearby Perth, Scotland

Ed Alverson, July 17, 2009, Finley Wildlife Refuge, nearby Corvallis, Oregon

Robert Kentta, July 18, 2009, Umpqua National Forest east of Roseburg, Oregon

Jeff DePonte, February 13, 2009, Kaluakauka, Hawaii Big Island